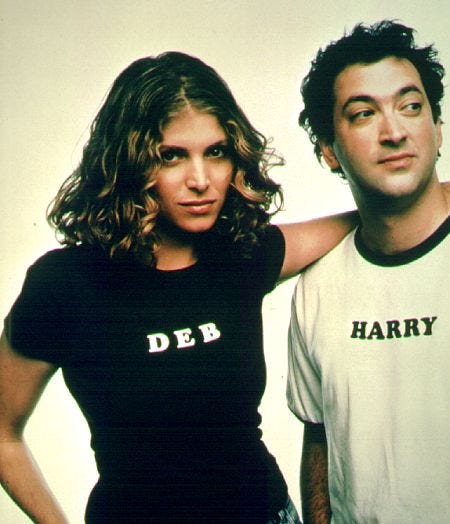

Upon realising that film-making duo Deborah Kaplan and Harry Elfont, who made one of the most iconic and recognisable teen films of my childhood Can’t Hardly Wait (1998) and the anti-capitalist cult classic Josie and the Pussycats (2001), had also been involved in the Brady Bunch remakes in the 90s, I immediately insisted that my partner re-watch them with me. It was a strange experience - as the opening credits ran, he abruptly announced that he had never seen the original Brady Bunch, and didn’t know anything about it. I paused the film while I explained the premise, while trying to think about whether the film would be as funny to him without understanding the premise the film was sending up. With this tone in mind, re-watching it was strange for a few reasons, but initially at least wondering what it was about the film that appealed to me so much when it seems highly unlikely I would have had any exposure to the original series either.

I have clear memories of multiple trips to the Blockbuster Video located on the major five-way intersection heading out of town towards our house, to repeatedly rent The Brady Bunch Movie (1995) and it’s sequel, A Very Brady Sequel (1996). We could later no longer use this Blockbuster after we unceremoniously had our membership voided when the store manager threatened to call the police as Mum refused to pay for a packet of Hubba Bubba Bubble Tape my little brother, just a toddler, had broken. I’ll never forget my mum’s righteous indignation, and my little brother’s palpable terror that he was about to be arrested, and I’m sure I must have mourned the loss of our membership but I just remember being so impressed by my mum’s fortitude. The Blockbuster would later close of course, although not before Mum and I took some videos back for our neighbour, and I idly wondered if the same store manager would be working there, and she was (she processed the returns for us with a smile, and I was flabbergasted that something so traumatic and formative for us had seemingly been so inconsequential for her that our stressed, pinched faces hadn’t even grafted to her grey matter).

The premise of the 90’s remakes are to transplant the Brady Bunch as they were in their 70’s hey-day into a suburban LA setting, using the simplistic moral code of a normative sitcom family to satirise both their nonsensical and once-aspirational existence with an America that has started to go to seed. I guess the series, absurdly popular - far more so than I realised - was ripe for a satirical send-up, with the family being a weird hangover from the more puritanical 50s/early 60s. Watching the original Brady Bunch, you had little awareness that around them that America was going through major cultural change, not to mention the Vietnam War. The film is laden with double entendres (‘well, I always know where to deliver MY mail, Mr Brady’) about how horny Mr and Mrs Brady are, as well as encounters with other characters that expose the Bradys’ hyper-naivete around alcohol consumption, sex, sexuality and beauty standards, and watching it as an adult, I can tell that most of it would have gone straight over my head (cue the knowing ‘ohhhhh’ after Marcia’s date Charlie, after being frenched on the doorstep, hurriedly leaves declaring ‘something suddenly came up!’).

It made me wonder what it was about the film that appealed so much (and what my parents used to think when we watched it) - it remains incredibly pleasing to watch. Anything associated with the family is deliciously retro, and subsequently the brightly coloured clothes and attention to detail in their family home makes for a film rich in aesthetic pleasure. However, what stood out to me the most on re-watching wasn’t any of the above, or how the film is now just as much a 90’s time capsule as it is for the original’s time period, but Marcia’s ‘best friend’ at school, Noreen.

Noreen’s big dyke energy jumped out at me urgently in her first scene, and although the film makes a point of portraying her explicitly as the doting friend whose affection is rooted in envy of Marcia and her beauty and status as ‘the prettiest girl in school’, the implicit but very clear coding of her as gay went straight over my head as a child. By the time we got to the scene where Noreen punches Doug for calling Marcia a ‘slut’, for which Charlie then gets to take the credit leading to him getting to snog Marcia, and Noreen crying because Marcia (obviously) wouldn’t know she defended her honour, I was still a little upset at myself for being so clueless about same-sex attraction that it didn’t occur to me a girl could have a crush on another girl. On the other hand, maybe it was a good thing that no one around me felt so strongly about lesbian stereotypes that they felt compelled to point out that futch woman in a bandanna and plaid shirt was that way inclined. I felt sure though, it now being 2020, that if I went looking someone would have already made this point in a funnier, more interesting way - and sure enough, not just anyone, but the current CEO of Autostraddle no less, have already written a piece in 2015 on Noreen and lesbian representation. And maybe it was possible that the environment in which a self-aware film like TBBM still traded in uncomfortable representations of queer people (as the only queer people in the film, no less) made it possible for representations like Regina George’s social ostracisation for ‘lesbian obsession’ of Janis Ian in Mean Girls, which came out 7 years later.

This is usually the point in which I am writing a personal essay that I lose enthusiasm and interest in what I’m writing about, because whatever it is I want to say and its perceived value usually withers away before my very eyes. I conveniently ignore the fact that there are, on any given day, several takes on a subject floating around, and that it is possible for more than one to be good. But something about the fact that I am not having a unique thought seems to shake my confidence enough that it no longer seems worthwhile. Luckily, I’ve just remembered that this is a free newsletter to which no one may ever subscribe so in which case it’s effectively just my journal, and I can carry on in whichever way I please.

What I’ve really been trying to get it is that my main takeaways from watching TBBM in 2020, the time of corona, were that a) I all of a sudden had a very urgent and vested interest in what happened between Noreen and the hot blonde girl at the end of the film (and was there likely to be any fan-fic), and b) that I couldn’t remember when I first met someone who was openly gay. The longer I thought about it, I realised that the only association I had with queerness before high school (where people were rumoured to be gay, some who later turned out to be gay, either openly or covertly) was my early years primary school teacher, who I distinctly remember was said to be gay. As with in high school, I have no recollection of this being relayed with any menace, or explicit homophobia, but at the same time it felt more like there was a void where gay exposure should be, and all the adults were just busy hoping that their period of obligation to talk about non-normative sexual desires passed, and then it was on us to work it out for ourselves.

I know I was homophobic, explicitly or otherwise. I built my self-confidence and personality throughout the tail-end of high school and into college on a tenuous and shaky foundation of apathy, communicated through shock-tactics to demonstrate the extent to which I didn’t care because if you didn’t care, then people couldn’t come for you about the things you cared about. Caring about things made you vulnerable, and I mocked vulnerability. I am sure there are plenty of people who have encountered my personal politics in recent years with a raised eyebrow, having known me around 2010. But nonetheless, I can’t help but have compassion for myself, being the kind of person at that stage who had sex with women but still felt compelled to tell people that ‘sometimes I watch lesbian porn, just because it’s nicer, you know’, the subtext being, please please please someone just give me permission to say I’m bisexual, it will save us so much time down the track. This permission didn’t come until much later (2014) and I frequently think of the stripper who was the first person I came out to in 2011, who must have been profoundly irritated by the emotional labour I demanded of her when I sat nervously by the dance floor, gesturing her towards me only to shout in her ear that I thought I might be bisexual. My friend and I were rightfully ejected from the venue shortly after this for being too drunk, and too broke.

I’m intending to now watch A Very Brady Sequel, which was the one of the two reboots directed by Deborah Kaplan and Harry Elfont, and I remember being a lot weirder. Carol’s ex-husband returns out of the blue, a character has a magic mushroom trip and Marcia and Greg make out (this quasi-incest is canon, to varying degrees, and the creators of the original show had to work hard to try and keep the cast from rooting one another to try and maintain a sense of familial distance, something that was made much harder by the fact the original Greg, Barry Williams, spent a big chunk of his post-Brady career sucking up airtime about how horny he was for Florence Henderson, who played his mum, Carol).

I promise to follow up accordingly.